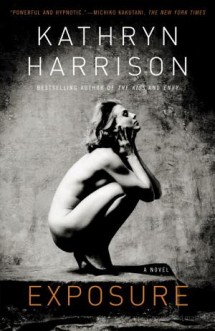

Chosen as a Notable Book of 1993 by The New York Times Book Review

ABOUT THE BOOK

Ann Rogers appears to be a happily married, successful young woman. A talented photographer, she creates happy memories for others, videotaping weddings, splicing together scenes of smiling faces, editing out awkward moments. But she cannot edit her own memories so easily–images of a childhood spent as her father’s model and muse, the subject of his celebrated series of controversial photographs. To cope, Ann slips into a secret life of shame and vice. But when the Museum of Modern Art announces a retrospective of her father’s shocking portraits, Ann finds herself teetering on the edge of self-destruction, desperately trying to escape the psychological maelstrom that threatens to consume her.

PRAISE

“A breathless urban nightmare not easy to forget. Stark, brilliant, and original work.” –Kirkus

“Powerful and hypnotic” Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“This astounding novel is built on ‘exposures’: what the camera lens does; how Ann’s mind opens and closes on her past, exposing the pain, then hiding it; how she was literally exposed to the world in her childhood and is again, in adult life, when her secrets are revealed. All this is told in prose as multifaceted as a diamond, crystalline and mesmerizing. Not often does a character breathe through a book’s pages, but the extent to which Ann Rogers is alive is almost scary. “Remarkable’ hardly goes far enough.”–Cosmopolitan

“A major talent. The book is taut in plot, beautifully realistic, and intelligently disturbing.”–Harper’s Bazaar

“At their best, stories expose the secrets we live with but cannot utter, and the best writers preserve the unsayable nature of those secrets while capturing them long enough for us to gaze upon their mystery. Kathryn Harrison is such a writer. . . . ‘Secure the shadow ere the substance fade” read the sign that used to hang above Ann’s great-grandfather’s shop. In this strong, wise, lyrical novel Kathryn Harrison has done just that.”–Chicago Tribune

“A mesmerizing depiction of a woman on the edge of emotional disintegration. Ann Rogers is a beautiful, chic, financially comfortable New Yorker with a career as a videographer of weddings and society functions, and a loving husband who restores landmark buildings. But Ann is addicted to speed, a drug which holds especially dangerous consequences for her, since she is a diabetic. Moreover, every time she does crystal meth, she compulsively shoplifts at Bergdorf’s and Saks. Flashing back to Ann’s Texas upbringing, Harrison gradually discloses the source of her deep neuroses. Her cold, monstrously selfish father extracted a bizarre kind of vengeance for her mother’s death in childbirth. Edgar Rogers became famous for his photographs of a prepubescent and adolescent Ann, naked and assuming deathly poses. He committed suicide in 1979; now a retrospective of his work, including photos of Ann engaged in acts the memory of which she has tried to repress, is imminent at the MoMA. Demonstrating impressive control of the novel’s structure and pacing, Harrison steadily deepens her sophisticated psychological portrait of Ann while elevating suspense and the reader’s emotional involvement. The shocking circumstances of Ann’s life become clear: she survived traumatic events by pathologically retreating into herself, but her subconscious erupts now and then in suicidal behavior. This unsparing picture of a woman spinning out of control is conveyed in luminous and tensile prose. The novel’s larger theme, an indictment of a society “which encourages exploitation even as it punishes all who chronicle it,” is eerily prescient, calling to mind the current controversy over photographer Sally Mann’s nude pictures of her children. Harrowing but spellbinding, the novel has the impact of an unforgettably vivid image seared on the eye.”–Publishers Weekly

“Ann Rogers seems successful–she’s happily married and a partner in a thriving videography business–but she’s also a diabetic hooked on speed and a compulsive shoplifter at some of New York’s best stores. While she skillfully videotapes and edits other people’s celebrations and turns them into happy memories, she is unable to face her own past. Her life spins farther out of control at the approach of a retrospective show at the Museum of Modern Art of the work of her father, a noted photographer whose model was prepubescent Ann, posed as if dead or caught in sexually explicit situations. Harrison is a remarkable storyteller with a clear, strong voice; she hooks the reader right from the start (as Ann tugs on a stolen skirt in a taxi) and shows, finally, that we are all products of our history.”–Library Journal

Reviewed by Wendy Smith, for The Washington Post

ALTHOUGH it opens with Ann Rogers slipping on her shoplifted green suede skirt in the back seat of a Manhattan taxi, then shows her scoring three grams of crystal methedrine from the receptionist at her successful video business, Exposure is not — thank God — a simple tale of overprivileged angst. As in her first novel, Thicker Than Water, Kathryn Harrison sets the personal story of a daughter’s struggle to deal with the psychic consequences of a disturbed family life against a sharply sketched social landscape that enriches the individual drama.

A short flashback sandwiched between her taxi ride and her arrival at Visage Video shows 16-year-old Ann, for more than a decade the subject of her father’s photographs, rejected as a model because her adolescent body too clearly displays the signs of adult sexuality. Edgar Rogers’s work (which inevitably brings to mind real-life photographer Sally Mann’s controversial pictures of her children) has depicted his daughter naked, seemingly dead, scarred by marks of self-mutilation. His photographs of Ann remain so incendiary that in the summer of 1992 a woman sets herself on fire in the Museum of Modern Art’s sculpture garden to protest its forthcoming Edgar Rogers retrospective.

Ann dreads the retrospective, although she has agreed to it as executor of her father’s estate, and her behavior becomes increasingly erratic and self-destructive as the opening approaches. She is careless about her insulin shots, continues taking speed although it worsens her diabetes-related health problems, shoplifts so blatantly that she is arrested. Her husband, Carl, who restores historic buildings, can’t tear down the wall of denial Ann has built around herself. “I am not a . . . renovation!” she screams when he tries to convince her that they must uncover the foundations of her pain and fear.

In counterpoint to the narrative of Ann’s unraveling, Harrison unfolds the complex fabric of her relationship with her father. We see her as a child desperately trying to learn more about her mother, whose death while giving birth to Ann left Edgar incapable of happiness or love for anyone else. The photographic sessions bring no real father-daughter intimacy; instead they create a stifling, claustrophobic atmosphere in which the aloof, mysterious artist manipulates a subject so alienated that she welcomes slipping into insulin shock, “the strange but increasingly familiar territory of her semiconsciousness [in which] the recording figure of her father became almost irrelevant.”

Ann thinks she can escape her father’s frightening demands by submitting passively to his camera but never sharing her thoughts and feelings with him. But after Edgar’s suicide in 1979 — he gave himself a lethal injection in the director’s chair on which she had stenciled “Papi,” taking six Polaroids of his death — Ann learns of the grotesque lengths to which he had gone to invade the areas of her life she tried to keep to herself. In the novel’s most shocking moment, Edgar’s dealer shows Ann an assortment of photographs her father had taken without her knowledge, images that violate the most basic notions of privacy and respect for individual dignity. This discovery sends the 19-year-old into an emotional and physical tailspin that foreshadows her 1992 crackup.

Harrison, who even in her first book displayed exceptional artistic assurance and control, has crafted a multilayered text that explores Ann’s ordeal from a variety of perspectives. She takes us inside her protagonist’s head for a first-person revelation of the emotional havoc wrought by a bizarre childhood, but she also creates judicial records, private detectives’ reports, business correspondence, newspaper articles and psychiatric evaluations to delineate other people’s responses to Ann’s actions. These serve a dual function: They add a cooler, more objective tone to the intense narrative; and, through the clever use of minor factual inconsistencies and occasional comments that reveal an observer’s ignorance, they remind us that the mysteries of creativity and the human heart can never be fully understood.

Unsettling questions about the limits of artistic freedom, parents’ power over their children and men’s attitudes towards women resonate beneath the surface of the text but are never explicitly explored, which is a shame. To my mind, Harrison’s work would have gained intellectual depth and excitement if she had openly confronted the larger issues raised by Ann’s life. It could be argued, however, that by concentrating on her attractive, intelligent heroine’s personal dilemma she has written a more accessible novel, and it is certainly true that any regrets about what Harrison chose not to do are more than compensated for by the reader’s pleasure in what she has accomplished: the delineation, in superbly modulated prose, of a woman’s painful, tentative journey toward self-knowledge.

PRIVATE EYE

By Vince Passaro, Passaro, whose fiction and criticism has been published in many newspapers and magazines, is working on a novel.

Kathryn Harrison, on the heels of her disturbing and elegiac first novel, “Thicker Than Water,” has written a second, “Exposure,” that plays off a newsworthy subject and creates an intense portrait of an artist’s (and a father’s) capacity for exploitation and betrayal.

The novel’s damaged and unraveling heroine is Ann Rogers, daughter of a renowned photographer, Edgar Rogers, who made his fame with morbid, suggestive and visually stunning black and white pictures taken of her when she was a child and a blossoming teen. The similarities of Ann’s situation to that of the children of the increasingly notorious photographer Sally Mann instantly suggest themselves: Mann takes beautiful and rather unnerving photos of her children — many of them, like Edgar’s of Ann, elaborately posed recreations of actual domestic moments, often involving death-like postures and various bruises and wounds. Childhood sexuality recurs also as a motif. A great deal of controversy has arisen about these photos; Harrison’s novel, aside from its considerable literary merits, contributes to that ongoing debate in tangential, dreamlike ways.

That Ann has been severely damaged by her father remains the emotional fulcrum on which the novel propels itself, although Harrison leaves room for an interpretation in which it was the man’s joyless distance and brutal disregard, rather than his art, that did his daughter in. Most likely it was both. The story takes place when Ann is an adult, marginally coping with her father’s suicide, which occurred when she was 19, her marriage and her career — she too is a photographer, and a partner in a successful videotaping outfit hired for weddings and such. She is also a diabetic, addicted to speed, a compulsive and very high-end shoplifter; her eyesight is going, a particular frightening side-effect of her condition, given what she does for a living, but this is not enough to get her off drugs or make her take minimal care of her health. She is falling apart at her job and letting her marriage slide into a chasm of secrecy and alienation. We observe her, through a series of third-person fragments, during the weeks leading to a major showing of her father’s work in the Museum of Modern Art, a show which will mark the first time many long-suppressed photographs — the most sexually explicit ones, of Ann as a teen-ager, masturbating, making out with her boyfriend, et cetera — will be seen. The show sends her into a frantic period of dramatic self-destruction, culminating, just after the opening night party, in a grand larceny that is sure to get her caught and does.

Harrison weaves into this story a number of other narrative voices, first-person memories of Ann’s childhood, court documents, letters and medical diagnoses, all of which point to Ann’s profoundly unhappy childhood. The overall effect of this cutting back and forth is appropriately disjointed and emotionally relentless, a narrative montage that mimics Edgar Rogers’ photographs, obsessive and unsettling. Harrison’s achievement resides in her coercion of her readers into seeing more — far more — of a painful life than we think we wish to see, a conviction that is itself belied by our fascination, our inability to stop looking, our refusal to turn away.

One of the bedrock strengths of “Exposure” is its corporal reality — Harrison mires Ann’s psychic dilemma in a tangle of physical details; each of her crises relates in one way or another to her body. For her diabetes Ann must twice daily measure her blood sugar and continually modulate her diet against the insulin she takes by injection in her thighs. She often fails to do this, and her history is one of using her disease, when she’s under severe emotional strain, as an instrument of near suicide. At the same time, being accustomed to dosing herself, it feels natural for her to treat her emotional incapacities in the same way she deals with her diabetes — fitfully, with speed, a quarter hit for low stress management, a half or full for anxieties higher on the scale. Her compulsive thievery too has a physical aspect; the clothes she steals become a kind of armor against a world she rightly sees as obsessed with looking at her; she makes herself a master of the quick change, often slipping off one outfit and putting on another in a moving taxi. She leaves the discards in the cab marking her trail.

And her central problem, her father, and his coldblooded use of her as an aesthetic object, denying her his love or even his basic friendliness as an equal human being, has an ultimate corporeal result: his photographs, gigantic prints of Ann and her mother (who died, hemorrhaging, in childbirth), close-ups of a wrist or a breast or a slashed and blood-dripping leg. The show at the Modern, which has so spun Ann out of control, is a landscape of bodily obsessions, the viewers’ eyes filled with Ann’s limbs and grimaces.

Harrison also makes you feel the chemical ebb and flow of Ann’s life, the almost hourly adjustments necessary to keep her functional. It is noteworthy, though, that she pays scant attention to Ann’s monthly shiftings, her menstrual cycle and its hormonal hit squads. This absence matches up with a kind of sexual freeze in the book: everything Ann does, the snouts-full of crystal math, the secreting of stolen objects, even the penetration of her body with hypodermics full of insulin, Harrison has charged with an underlying sexual tension and suggestiveness; but actual sex, desire itself, remains for Ann distant and strange. This, presumably, is Harrison’s conscious method, accurate in terms of the abuse Ann has suffered. The body obsession of “Exposure,” even taken to these extremes, or especially so (for that is its achievement), feels overpoweringly familiar and shameful.

In its frightening, fragmentary and almost hallucinogenic visions, Harrison’s writing reminds you of a kind of 1970s sensibility, in which personal loss is devastating and unnameable, and the major routes of self-destruction are chemical and illegal. Exposure in turns recalled for me Joan Didion’s “Play It As It Lays” and Kate Braverman’s astonishing first novel, “Lithium for Medea,” both books of the mid-to-late 1970s. The clipped and ironic understatement also remind one of Didion, a sharp intelligence taking the measure, hopelessly, of an absurd and sinister universe. This personal universe, like the larger one, inexorably expands. It catches you in it and sends you bounding out into a limitless darkness, a fearsome void. That Harrison has accomplished this, twice now in as many tries, marks her as one of the most promising new writers of her generation.

Kathryn Harrison’s troubled families; Novelist explores the sinister side of parent-child relations By Joseph P. Kahn, Boston Globe Staff

Like a teen-ager rummaging through her mother’s cosmetics case looking for just the right shade of lipstick, Kathryn Harrison fumbles for a remark by William Faulkner that she first encountered 20 years ago.

“Don’t quote me on this,” Harrison cautions, “but I think Faulkner said something like, ‘One ode from Yeats is worth any number of old ladies’ lives.’ I was shocked by that. I mean, is that true? Is art really really worth any number of lives? Even one? In this society we give art a great deal of power, but where does it cross over the line into exploitation? I don’t know the answer to that.”

Except for crossing burglary with homicide and Keats with Yeats, the remembered quotation is close enough. Faulkner, observing that a writer’s only true responsibility is to his art, actually said, “If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ is worth any number of old ladies.” Harrison’s point is not only well taken, however, it is also the thematic key to her critically acclaimed new novel “Exposure,” one of the hot properties of the publishing season.

Ann Rogers, the novel’s heroine, is a troubled young woman coming to terms with a dramatically troublesome past. Her father became a high-profile art photographer by using Ann as his model, often shooting the child in sexually suggestive poses and frequently, as Ann discovers after his death, without her knowledge that the camera was pointed at her. Robbed of any childhood innocence, Ann turns to compulsive shoplifting and drug abuse to act out unresolved feelings of guilt, anger, violation, complicity and, yes, love. The higher her father’s reputation soars, the lower Ann’s self-esteem sinks into a funk of self-destruction.

“Exposure” appears two years after “Thicker Than Water,” Harrison’s debut novel, which was also warmly received by critics. In it a young woman named Isabel struggles to make sense of two fatally compromised relationships: one with her dying mother, who sexually abused and emotionally abandoned her, the other with a mostly absent father who later forces her, at age 18, into a savagely incestuous relationship.

“This is a story about desperate women and their unhappy destructiveness,” says Isabel, in what effectively serves as a coda for both of Harrison’s works.

One might infer from her darkly mottled prose that lunch with Harrison at the Ritz would be about as sunny as high tea in the kitchen with Sylvia Plath. Not so. At 32, and now the mother of two young children herself, Harrison is an attractive, witty, vibrant and upbeat woman who seems a bit stunned by her own success, yet reasonably unconflicted about her life – or art. And while elements of her novels (particularly the first) are admittedly autobiographical, she is not on book tour to do a Donahue as America’s newest diva of dysfunction.

“I’ve always defined myself as hopeful,” Harrison insists. “My expectations may be pessimistic, but I’m hopeful as a person. And as a writer too, I guess. My characters seem to have that stubborn hopefulness in them as well.”

She was born and raised in Los Angeles – “born facing east,” she says, by way of pinpointing her cultural orientation – in an old, rambling house on Sunset Boulevard that belonged to her maternal grandparents. Like Isabel’s, Harrison’s father pulled a disappearing act when she was extremely young. Her mother, 18 when Kathryn was born, chose to get on with her own life and not be bothered much by the burdens of motherhood. Harrison’s grandparents, who raised her, had lived as Brits-in-exile in Shanghai and ran a household singularly unreflective of the LA-Hollywood culture that surrounded them.

“I was a little girl in a big house living with two old people, by myself,” she says. “It was almost antediluvian. I read voraciously and poked around through old boxes of photographs, which totally seduced me. In many ways I had a childhood that was, if not comforted, sort of saved by the companionship of books.”

Intending to pursue a premed major, Harrison entered Stanford University and subsequently switched over to concentrate in the humanities. Three years later she was accepted to the famed Iowa Writers Workshop, where she met her future husband, novelist and editor Colin Harrison. They moved to the New York City area in 1987 and now live in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn. She landed an entry-level job at Viking and apprenticed under editor Nan Graham for three years. At the same time Harrison was rising at 5 a.m. to work on her own fiction, never letting on to colleagues that she led a secret literary life. Her family back in LA was even more confused.

“To them being a writer meant being a journalist,” she says, plucking an oyster from its shell. “My grandmother somehow decided I was going to be an anchorwoman. She assumed I had moved to New York to become the next Jane Pauley.”

With 150 pages of “Thicker Than Water” completed, Harrison applied for and won a Michener Fellowship. Later, with the encouragement of both Graham and Michael Pollan, a colleague of her husband’s, she submitted her work-in-progress to star-maker agent Amanda (Binky) Urban. The Michener award had been “an important validation,” says Harrison, but finding Urban was a revelation. Urban received the manuscript on a Monday, phoned the author on Thursday (“I couldn’t believe she was inviting me over to reject me in person,” quips Harrison) to give her the thumbs-up and, by the following Monday, had secured a preemptive bid from Random House.

So much for the agonies of first-time authorship.

“It was wonderfully fast and painless,” admits Harrison, “and very few writers can say that.

Her mother’s death marked a turning point in Harrison’s young life. At 39, her mother contracted breast cancer, which quickly metastisized into bone cancer. Harrison moved back to California to help care for her. Three years later, after a painful and debilitating morphine-laced siege, her mother passed away. Harrison concedes that death arrived before mother and daughter could achieve the sense of closure that she herself so desperately wanted and pushed for.

“My mother, who had dabbled in all sorts of religions, was terribly slippery and resistant to the end,” says Harrison quietly. “However, the needs of the living and the needs of the dying are not the same. My mother was departing. Many of the things I found compelling – even essential – to understand were things she no longer felt the need to. I used to sit by her bedside, boiling over with desire to discover things.”

Things about her mother and father especially. With Isabel, Harrison adds, “I wound up creating a fictional scenario of conflict and closure that never existed for me, to my everlasting frustration.”

Though less explicitly autobiographical, “Exposure” is in many ways a slicker and more accomplished take on a similar theme, the sinister side of the parent-child relationship. Here Harrison’s focus is on the art of photography as an instrument of rape and plunder. While echoes of the work of Sally Mann and Jock Sturges seem natural, Harrison maintains that it was more the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe that got her thinking about what happens when the most intimate, personal images are sent out into the world for mass consumption.

“Like Mapplethorpe’s work, what Ann’s father has created is clearly art,” she says. “But does he have the right to appropriate or damage her life? That’s the question that haunted me. I believe there is no clear directive saying where to draw the line, but I also believe any writer or painter or photographer who uses his or her own children as subjects must ultimately face this issue.”

The flip side to this question, says Harrison, is the extent to which Ann becomes a willing conspirator in the artistic process.

“After all,” she says, “her mother died when she was born. She wants her father’s love. This may be a costly way for her to buy it, but it also seems worth it to her.”

For Harrison, who is well into a third novel (set centuries ago, at the end of the Spanish Inquisition), the spotlight of attention is beginning to widen at a time when she seems more determined than ever to balance authorhood with motherhood. There is a good chance “Exposure” will be optioned to Hollywood, for instance, leading to the enticing possibility of one day seeing Harrison’s name on a billboard high above Sunset Strip, reflecting down on the scene of earlier crimes and misdemeanors.

“I’m beginning to understand that my life will have this imbalance,” she sighs. “I go for months or years working in solitude, with no feedback. Then I get all this feedback at once. There is a certain vertiginous quality to it that can get daunting for someone like myself, who is essentially a pretty private and introverted person.”

She smiles and stirs her espresso. “I have a family now,” she says, finally. “Their lives are worth everything to me.”

———————————————–

The Twisted Family Plot; Kathryn and Colin Harrison: Behind the Dark Novels, a Sunny Marriage

Jay Mathew, Washington Post Staff Writer

Colin Harrison, newly hot New York novelist, waited until Page 10 of his latest book to murder brutally a woman who closely resembles his wife, Kathryn Harrison, also a newly hot New York novelist. It is not pretty, but then little of what the Harrisons write is.

What is certain is that as Liz waited for the light, a silver BMW with tinted windows — in my nightmares, it is a sleek, fantastic vehicle of death, gliding noiselessly through wet, empty streets, colored lights sliding up the dark windshield — pulled over and someone poked the short metal barrel of a 9mm semiautomatic pistol over the electric window and started shooting.

Colin Harrison writes late at night on a Coca-Cola caffeine high that fuels a nerve-jangling vividness. He does not spare the reader the image of a bullet shattering the head of the woman’s unborn baby, or the pimples on the face of her corpse, or a dozen other details a wife and mother might not like to see in print.

But his spouse can match him — may indeed exceed him — in klieg-light exposure of gray-white mushy objects better left under rocks. In the Harrison household, a four-story brownstone in Brooklyn littered with papers and children’s toys, the simmering stew of gore and pain and regret is simply what Mommy and Daddy do for a living.

How such an ordinary, seemingly happy existence can produce such jarring, claustrophobic books is as much of a mystery as the souls of the Harrisons’ haunted characters. They reveal something about art that often searches for the other side of the moon, a subject to feed upon as far away as possible from the natural and the expected.

The contrast of humdrum reality and upscale nightmares seems to be working for the Harrisons. They have each just published a warmly reviewed second novel and seem to have achieved an extraordinary personal and literary hat trick — balancing marriage, parenthood and an almost obsessive need to write.

Publishers Weekly called Kathryn Harrison’s new book, “Exposure,” “a mesmerizing depiction of a woman on the edge of emotional disintegration.” It was selected as a Book-of-the-Month Club featured alternate, a good sign for an untested young novelist.

Colin Harrison’s new book, “Bodies Electric,” is being heavily promoted as the flagship thriller of a new generation of writers. The Kirkus review said that “what might have been a routine corporate-basher becomes, in the hands of a very skillful, wisely observant, and profoundly moral author, a novel to remember.” The New York Times said that “to label it a thriller is like calling ‘Hamlet’ a murder mystery.”

Dredging the darkest, most terrifying aspects of family life seems no more troubling to the couple than cleaning out the spare bedroom. Kathryn was very pregnant when her husband took one of his legal sheets and scribbled the murder of the very pregnant, very Kathrynlike Liz Whitman in “Bodies Electric.” Of this delicate moment in her marriage, Kathryn said, “I think we write out of our fears, and I knew that Colin wrote that because he loved me. One of the things he’s really scared of is that something is going to happen to his family.”

Kathryn’s own work would win no prizes from the PTA. “Exposure” is the story of a young woman facing a breakdown as she remembers the disturbing poses her photographer father forced her to assume when she was a child. A cataloguer describes one photo:

Two children, a girl and a boy approximately 12 years of age, outdoors, in a crude wood structure nailed to the boughs of a tree in full summer leaf. They are naked. The grain of the photograph is evident and suggests the use of a telephoto lens, giving the image a stolen, documentary quality. The girl lies full-length on top of the boy, whose face is turned up toward hers; his neck strains so that the muscles are corded and the veins swell slightly. Her bright blond hair falls across their joined mouths and closed eyes, her hands cover his ears. While the image is not explicit, the children appear to be involved in sexual intercourse.

“We used to joke about Kathryn dropping off her daughter at the toddler school and then going home to write about these exquisite tortures,” said Kris Dahl, Colin’s literary agent at International Creative Management.

The Harrisons are still young, both 32, and relatively unknown. All sorts of mundane obstacles lie in the way of their ambitions. Furthermore, their relationship and living arrangement defy literary convention.

If Joyce Carol Oates married John le Carre, or Thomas Harris set up housekeeping with Judith Guest, wouldn’t the world expect the romance to break down in short order? The assumption is that novelists — particularly those whose work is as intense as the Harrisons’ — need solitude and perhaps quiet, nurturing, nonliterary spouses.

There is also the matter of their very different backgrounds — Kathryn raised by strict and somewhat chilly grandparents when her mother abandoned parenthood, while Colin enjoyed the warm and gentle upbringing of an actress mother and an educator father who is now head of the Sidwell Friends School in Washington.

Can this marriage endure? Close observers watching for the slightest sign of strain cannot see even a quiver.

Indeed, not only does the Harrison marriage seem to work splendidly on a personal level, it works on the creative level as well. Their muse, if it ever took earthly form, would resemble a schoolmistress with a sharp ruler. Wife and husband are wedded to the notion that inspiration does not come unless you sit at your desk and write every day, no excuses, no distractions.

They remember other gifted writers they met at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where their own romance began. “One thing you learn in retrospect is that the presence of talent means nothing,” Colin said. “There are some people who have left their talent on the table.”

Colin, who had summer newspaper reporting jobs during college, is a data collector. He interviews experts and assembles information like a mad archivist. The stacks of newspaper business sections grew so high while he was fashioning the corporate intrigue in “Bodies Electric” that his wife began to complain about the fire hazard.

Kathryn is more emotional and internal. Once at Tiffany’s, trying to imagine how the shoplifting heroine of “Exposure” would feel, she became so overwrought she had to leave the store. “My heart was pounding so fast — I was afraid I’d actually try to steal something,” she said.

She excels in the matter-of-fact violation of taboos. The central character in “Exposure” addresses her dead father:

Your ashes were returned to me in a heavy-gauge black plastic box whose lid would not yield to the pressure of fingers but had to be pried open with a knife… . I poured the ashes out into a bowl and looked at them. Dug my hand into what was left of you. It came out gray. I licked my palm, and then I had taken some of you inside me. What I wanted was to sit with my bowl and a spoon and eat you up, grind what was left between my teeth.

Colin is a former soccer player and intense racquetball player whose books lean more heavily on plot and dwell on robust, American virtues that go wrong. His principal character in “Bodies Electric” says, “I was happily spinning beneath the sky with a beautiful woman and child, unmindful that I was in good health, unmindful that I was making three hundred and ninety-five thousand dollars a year. Enough money, as I have said, to make my father wince. But I did not know what torments awaited me and, more to the point — to insert the rigid steel needle of truth into the soft marrow of happiness — I did not know how I would torment others.”

The Harrisons met at Iowa in 1985. Colin had grown up in Westtown, Pa., the son of Earl Harrison Jr., then headmaster of the Quaker boarding school there, and Jean Harrison, an actress who often enlisted Colin and her younger son, Dana, to help her rehearse. Dana now teaches science at the Landon School in Bethesda.

Colin graduated from Haverford College, just 15 miles from Westtown, determined to be a novelist. He carried a lump of a manuscript with him to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He was in his second year when he attended a reading by an intriguing new student from California.

Kathryn had grown up in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles with her grandparents. Her mother, only 19 when Kathryn was born, made no secret of her distaste for child-rearing. Her father had left shortly after the birth. Raised mainly by her strict and very British grandparents, she was a studious and sheltered child. She studied English and art history at Stanford and then returned to Los Angeles to help her grandmother cope with the fatal illnesses of her grandfather and mother before going to Iowa.

There, she seemed “very aloof and very vulnerable,” according to novelist Bob Shacochis, one of her professors. Her writing was “very Latin American, very European, not trendy at all but brilliant.” She would concentrate fiercely when they worked on her stories and then, sometimes, burst into tears.

Colin heard her read one of her stories, a characteristically stark account of Jayne Mansfield losing her head in an automobile accident. He walked up and offered some helpful criticism, the standard pickup line at a workshop. A few days later he invited her to lunch.

At lunch, he was surprised and pleased that this writer so obsessed with horrific themes had “a terrific sense of humor.” She liked his self-assurance. “If you run into Colin and you don’t like him, you receive the message of, well, I like myself and you’re missing out on something good because I’m very charming,” she said. In what Kathryn calls “a shockingly short period of time,” she moved into the house he was renting. He stayed an extra year teaching and writing while she finished the two-year program. Then they went to New York.

Two successful novelists can live almost as cheaply as one. The Harrisons are now down to just one day job — that being Colin’s position as a senior editor at Harper’s. He started with the magazine shortly after an agent who no longer represents him read his new crime thriller, “Break and Enter,” and said it wasn’t to her taste. He sent it to David Groff, an editor at Crown who had once passed through Iowa sampling student wares. Groff bought it immediately. “It was incredible stuff,” he said. “We are not used to seeing morally profound books on popular subjects.”

Kathryn approached her first novel, “Thicker Than Water,” more haphazardly. “For a long time it was just these scattered pages. I didn’t know what the beginning was. I didn’t know the end.” She won an $ 8,000 Michener fellowship in 1989 to complete the manuscript.

Whatever drives the Harrisons has not relaxed since their commercial future began to look promising. At lunch he leaves the magazine office and crosses the street to sit in the VG Bar-Restaurant with his pen and legal sheets. The waitresses bring him his Coke without ice and leave him to write. When a deadline looms, he kisses Kathryn goodbye and checks into a cheap Long Island motel with his computer for a typing orgy.

During quieter times the work follows a routine. After their 3-year-old daughter and 1-year-old son are in bed, Colin climbs to the third floor of their brownstone and wedges himself into his office — a walk-in closet littered with drafts. “I like the compression,” he said. Her office is just down the hall. It is very narrow, but with a window.

Her writing day begins at 9:30 a.m. when the babysitter arrives. She eats lunch and plays with her children and then goes upstairs again until 5 p.m. Weekends are spent with the children. The Harrisons do not entertain very often. Most Saturday nights they are upstairs tapping away.

“A family is an energy system,” said Colin. “We are very cognizant of what’s happening to the other person and who is on the front of the stove and who is on the back of the stove. Right now Kathy’s on the front. She’s putting some pages together to sell her new book, and as soon as she does, we switch positions.”

“Colin’s characters typically begin with everything and somehow contrive to lose it all,” she said, “and my characters begin with the decks stacked completely against them and when you get to the end of the book there is some sort of hope that everything is going to be okay.”

“You are redemption,” he said, “and I am tragedy.”

READER’S GUIDE

1. Exposure’s epigraph reads: “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.” (Diane Arbus). What sort of meaning did this quotation have for you before you read the book? What about after you finished Exposure?

2. Unlike the typical chapter-by-chapter format, Exposure switches between the present and past, alerting us to changes in time and place by specific section markers. Harrison also includes unmarked sections, with sections of newspaper or Ann speaking in first person narrative. What did you think of this structure? How did it help you to understand the story, and Ann as a character? What do you think would have been different about the novel if it was written in a chapter-by-chapter structure?

3. Discuss Ann’s relationship with her father. What kind of relationship, if any, did they have outside of artist/model? Do you think Edgar was abusive? Where do you draw the line between art and abuse?

4. Harrison describes Edgar’s photographs in great detail, even though their subject matter is highly controversial. What are we to make of these photographs? Do you think Harrison is making a comment on the voyeurism of our society? How and why or why not?

5. How does the early death of Ann’s mother influence her? How does it affect her father? Do you think Edgar blames Ann for the death of his wife?

6. Discuss Edgar’s sister, Mariette. How does she fit into Ann’s family? What kind of support does she provide for Ann?

7. How does Ann use her diabetes to manipulate other people? What do you think Harrison might be trying to say here about power struggles between individuals? Do believe that both weakness and strength provide currency? If so, does this equalize them on some level?

8. Discuss Ann’s occupation as a videographer. How does it compare and contrast with her father’s work? Do you think she made a conscious decision to work in photography, or do you think Ann would view her work as completely different from her father’s trade? Is she trying to overcome her past through her present work? If so, how?

9. Where you surprised by Ann’s drug use, given her diabetes? Why do you think she becomes addicted to amphetamines? Is Ann a self-destructive character or is she just deeply troubled?

10. Does Edgar’s documenting his suicide make it more performance than private act? Do you think the way he chose to die was meant as a message to his daughter? If so, what would that message be?

11. Describe Ann and Carl’s relationship. How do they work, as a couple? What does each of them bring to the relationship? Are you surprised by Carl’s behavior at the end of the novel? Do you think his marriage to Ann will survive?

12. What role does shoplifting play in the novel? Discuss Ann’s stealing and the repercussions (or lack thereof) of her behavior. In certain narratives – fairy tales, for example – a character’s changing clothes has symbolic meaning. What is the significance of Ann’s changing into stolen clothing and leaving her own clothes in taxi cabs?

13. Ann’s doctor tells her if she doesn’t start taking care of herself, she may go blind. What does this loss of vision signify for Ann, beyond being unable to work?

14. Edgar’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art drives Ann to an emotional crisis, yet she has always been troubled by her childhood and her relationship with her father. What is it about exhibit that disturbs her so? What does she consent to help pick the photographs to be displayed and agree to be in attendance at the opening?

15. What did you make of the novel’s ending? Is it genuinely hopeful? What do you think the future holds for Ann?