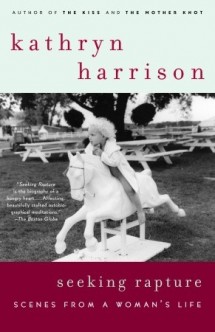

ABOUT THE BOOK

In this exquisite book of personal reflections on a woman’s life as a child, wife, and mother, Kathryn Harrison, “a writer of extraordinary gifts” (Tobias Wolff), recalls episodes in her life, exploring how the experiences of childhood recur in memory, to be transformed and sometimes healed through the lives we lead as adults. At the heart of Seeking Rapture is the notion that a woman’s journey is a continuous process of transformation, an ongoing transcendence and re-creation of self

PRAISE

“Diabolically compelling. . . Harrison is daringly confessional and ravishingly poetic in her re-creation of her stressful California childhood, during which she did not know her father and slavishly worshiped her young, glamorous, ice-queen mother while her maternal grandparents raised her with a bewildering mix of quaint strictness and unintentional laissez-faire. No reader could ask for a more intriguing figure than Harrison’s grandmother, who was born Jewish and raised in Shanghai, and the evolution of their complex love plays in plangent counterpoint to Harrison’s tragic failure to win her mother’s affection. Harrison’s family portraits are vivid, involving, and resonant, as is her frank chronicling of her unhealthy beguilement with the martyrdom of women saints and her corresponding anorexia. Unfortunately, Harrison veers from the courageously cathartic to the dismayingly aberrant in excessive and creepy broodings over ticks, head lice, and cat births, oddities that detract from her otherwise lancing inquiry into longing and loss, fetishistic mourning and brute survival, and, finally, the miracle of munificent love.”–Booklist

“Seeking Rapture is the biography of a hungry heart. . . . Affecting, beautifully crafted autobiographical meditations.”—The Boston Globe

“Revealing . . . [Harrison] has produced enthralling essays that bring to mind the robust metaphysics of Kathleen Norris and Patricia Hampl. Kathryn Harrison has challenged herself—and won—with her passionate, rigorous thinking on family bonds and family bondage, and the mysterious intersections of body and spirit.”—The New York Times Book Review

“[A] rich collection . . . Harrison aims, over the distance of time and often with dazzling accuracy, for unflinching display of motivations. . . . Such fastidious recall is a Proustian gift. With all due regard for her achievement as a novelist, Harrison appears Proust-like in another respect: She is her own truest subject, an unending wellspring of emotion and restless quest.” —Los Angeles Times

“Harrison remains a master of her craft, with musings that are lyrical, insightful, and haunting.”—Entertainment Weekly

“Poignant glimpses into the life of a survivor.”—Kirkus Reviews

“The prose sings….Harrison [is] at her thoughtful, provocative best, mindful of the flaws and desires within everyone.” —Publishers Weekly

Kai Maristed, Special to The Los Angeles Times

Before our current, enlightened age of child-rearing, parents driven to distraction by their offspring’s whining were apt to threaten a grim proportionality: “You pipe down, or I’ll give you something to cry about!”

Kathryn Harrison, who burst into full frontal literary view with her fourth book, “The Kiss,” an autobiographical account of a father-daughter affair, is certainly nobody’s crybaby. At 9 she cauterized and skinned her tongue with dry ice; at 15 she starved herself (in her horror of carbohydrates, even spitting the Communion wafer out in her fist) from solid to Twiggy-thin. She has given birth to three children without analgesics. (Coincidentally, we are sisters in this last, and I can attest to the unembellished accuracy of her report, “Labor.”) But Harrison, grown up and looking back, will not pipe down.

Judging by the 17 essays collected in her new volume, “Seeking Rapture: Scenes From a Woman’s Life,” every turning of her girlhood held a surfeit of pain-filled things, long before the seduction by the prodigal father. Through childhood, aggressive silence was her chief defense. Now Harrison aims, over the distance of time and often with dazzling accuracy, for unflinching display of motivations. She orders the chaos of memory under a klieg light of confession from which no detail, least of all the humiliating or bizarre, can hide.

“Since the same woman raised us, mine was not the typical Los Angeles childhood any more than my mother’s had been. My grandmother emphatically disapproved of all things American and encouraged me to form myself in contrast to the children around me.” Leaving aside the dizzying question of how one defines the “typical Los Angeles childhood” — aren’t thousands of kids being raised here at this moment by their doughty grandmas? — this remark holds a key to the future author’s development. The Nana in Harrison’s case is a splendid character, a full novel’s cast in herself. She was ” ‘born a Jew’ … ancestry being one of the inconveniences she feels she has overcome” and subsequently “cared for” on a sumptuous estate in Shanghai’s International Settlement before entering a tempestuous career as unattainable flirt and heartbreaker.

Nurture wins hands-down over nature as young Kathryn, only child of the only child of this volatile refugee ex-pat, grows up under grandmother’s aegis. Proud, yearning and loathing of her own perceived imperfections, she is marked by the unearned punishment of flighty parents conspicuous in their absences. The “primal scene” in these psychogrammatic sketches from a young life is surely that of Mother moving out for good. Kathryn’s 6-year-old heart simply breaks on the wheel. “In the afternoons I sat in the closet of her old room, inhaling her perfume from what dresses remained; each morning I woke newly disappointed at the sight of her empty bed in the room next to mine.”

Written decades later, it is an excruciatingly poignant reliving. Many of the pieces in “Seeking Rapture,” whether they were composed with a unifying theme in mind or not, chronicle and catalog the symptomology of early loss. “Keeping Time” concerns a hoard of watches and clocks and the punctuality imperative, the title essay (the collection’s richest) connects renunciation, self-mutilation, conversion and power in a child’s mind, “The Supermarket Detective” confesses teenage binge-shoplifting without a dollop of shame.

Other pieces parse Harrison’s adult record vis-a-vis her own children — where she has battled to make amends for the sins of her parents, where she has fallen short. And where she has succeeded in loving. Topics of this kind seem to figure prominently in the current American zeitgeist: While reading “Seeking Rapture,” I chanced on a biographical piece by Judith Thurman on the performance artist Vanessa Beecroft. Beecroft is a self-outed exercise bulimic whose acclaimed staged “events” often involve near-naked fashion models and whiffs of sadomasochism.

Beecroft grew up with a demanding, childish mother; her father left when she was 2. Taking a step back for perspective, Thurman muses on how a human being’s early emotional starvation is dealt with either defensively by self-starvation or aggressively by accomplishment and seduction or both — but always with a sense of hollowness at the core. For a moment I thought Thurman was responding to “Seeking Rapture.”

The excellent news for Harrison, if nowhere explicitly stated as such, is the way circumstances drove her on the one hand to find release in art, specifically in writing, while on the other providing her with superior tools: a good parochial school education, a dose of cultural elitism, a childhood addiction to books. Her writerly powers range from forte to delightful pianissimo, as in this description of a spinster attending a cat fanciers’ meeting: ” … spinning [cat]wool in her lap while the other women talked and ate. If she sat in a beam of sun, cat hair floated in the air around her, settling onto the surface of her untouched coffee.”

Such fastidious recall is a Proustian gift. With all due regard for her achievement as a novelist, Harrison appears Proust-like in another respect: She is her own truest subject, an unending wellspring of emotion and restless quest. If to write means to share the full measure of one’s experience, any reader of these essays is well-served.

——————————–

From THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

A child paints her universe in primary colors — parents loom as either God or the devil — until time, or a stint of therapy, unmasks them as simply and absurdly human. But as Kathryn Harrison revealed in her 1997 memoir, ”The Kiss,” her parents played both of these cosmic roles far too convincingly. Once she was divorced, Harrison’s glamorous young mother wanted no hindrances to a new dating life. So she left her 6-year-old daughter for her own mother to raise and then, like a fickle goddess, made cameo appearances in the worshipful child’s life. Harrison’s absent father swept back into his daughter’s sight when she was 20. In her memoir, she describes him as a rapacious and slightly mad preacher who preyed on her childhood of longing for him and led her into a furtive sexual bond, invoking God as the third party in the relationship.

Possession — by eros, by obsessive religiosity, by a ravenous parent or a violent act in the past — has shadowed not only Harrison but also her female protagonists in novels like ”Exposure,” ”Poison” and ”The Binding Chair.” And now, in ”Seeking Rapture,” her first collection of personal essays — some new, some previously published in The New Yorker and other magazines — she again probes the turbulence of her past, this time tempered by the redemption of a placid life with her husband and children. But the blunt facts of Harrison’s history forbid any mushy idealization of childhood or sentimental worship of the ”maternal instinct,” granting these essays a crisp and unencumbered candor. Harrison is particularly revealing as she describes her fraught transactions with dailiness — freezing at the prospect of shopping for furniture to establish her own household; unnerved by conversations with her 5-year-old daughter about sex and death. Her essays examine love within a family, not just the dependable ordinary variety but the extreme renditions in which affection hardens into idolatry, with one human mistaken for a god and another cast as a supplicant.

In the essay called ”Keeping Time,” Harrison confesses that she has filled her home with an army of small black alarm clocks — still captive to a mother who lived ”in flagrant disobedience to time. . . . It wasn’t that she was late in any prosaic sense. No, in tardiness, as in other areas, she was grand, extravagant, epic. Late by an hour, a day, a season.” This left her daughter eternally waiting, ”always the last to be picked up from birthday parties, Sunday School, ballet class.” The arrival of her mother’s turquoise Pontiac brought little solace. ”Filled with clothes shrouded in dry-cleaning bags, an overnight case,” the car ”announced itself as the vehicle of a fugitive,” with Harrison never in doubt as to whom the fugitive was fleeing. Catching one ray of everyday life and spinning it into a shrewd contemplation of emotional treachery, Harrison conceives a portrait of narcissism so entrenched, so reflexive, it feels innate, like the color of her mother’s eyes.

Harrison’s grandmother was no June Cleaver either. Nana was the autocratic queen of the Los Angeles wing of a clan of wealthy, French-speaking British Jews, ”a woman given to yelling, ‘I’ll eat you up! I’ll have you on toast!’ ” She also required her granddaughter to ”curtsy like a proper British child” from the age of 2.

Harrison soon discovered a neat escape hatch from her agonized mother-longing. The title essay recounts her mother’s weekend flings with Roman Catholicism and Christian Science, describing Harrison’s youthful initiation into the giddy elevations of spiritual rapture. After a car accident, her unusually solicitous mother rushes her to a Christian Science practitioner, who cradles the child’s head in her lap. ”The top of my skull seemed to be opened by a sudden, revelatory blow and a searing light filled me. . . . I felt myself no more corporeal than the tremble in the air over a fire. . . . I stopped crying. My mother sighed in relief, and I learned, at age 6, that transcendence was possible: that spirit could conquer matter, and that therefore I could overcome whatever obstacles prevented my mother’s loving me. I could overcome myself.”

In the ensuing years, Harrison labors to repeat this ecstasy. She enacts exultant rituals of self-mutilation, like applying dry ice to her tongue until it bleeds. Next she progresses to a zoned-out anorexia as she woos her sleek, thin mother by trying to carve a matching body. Poring over technicolor images of the ultimate good girls, the female Catholic saints, with their ingenious stratagems for self-abasement (St. Veronica may be the winner: she washes the floor with her tongue), Harrison finds religious reasons for her self-mortification. Like the saints, she sets herself the goal of blotting out the sinful earthly body in order to be swept into ecstatic union with the Beloved. Her ritual penance continues into early adulthood.

Later, this theology, which fiercely divided the world of matter from the realm of spirit, loosens its grip on her. In ”What Remains,” she contemplates the peculiar relics that are worshiped after death, from Mother Cabrini’s dentures to Kurt Cobain’s bloodstained guitar, and recalls the fragments of her own family that she preserved — her grandfather’s shoe trees; her mother’s baby teeth, the scarf her grandmother wore as she lay dying. These tokens of mundane matter, like her grandmother’s ashes, are now ”made holy to me by love and by blood.” To enter the spiritual, she has come to understand, does not demand denial of the earthbound.

In the last essay, Harrison describes the way her children have helped to close the divide. She recalls how, after her mother’s death, ”I tried to imagine what the circumstances might be that could tempt me back into a posture of supplication. As it’s turned out, I bow my head eagerly. Each night, by their beds, knees mortified by Lego, elbows planted among stuffed animals, I’m being rehabilitated.”

On occasion, Harrison’s writing can be cloyingly melodramatic, as when she likens a tick’s belly to a ”lunar landscape” of loneliness. But for the most part, she has produced enthralling essays that bring to mind the robust metaphysics of Kathleen Norris and Patricia Hampl. Kathryn Harrison has challenged herself — and won — with her passionate, rigorous thinking on family bonds and family bondage, and the mysterious intersections of body and spirit.

Deborah Mason is a writer and critic who lives in New York.

——————————————-

AMANDA HELLER for THE BOSTON GLOBE

If parenthood is a struggle to avoid repeating what our elders did to us, then for the writer Kathryn Harrison, parenthood is an all-out war to eradicate the past. The cheerful nursery mess underfoot as she anxiously patrols her sleeping children’s bedroom is a deliberate indulgence, an antidote to the emotional deprivation that scarred her own girlhood.

“Seeking Rapture” is the biography of a hungry heart. Born into a shotgun marriage that lasted only a few months, the author was raised by disapproving grandparents grimly determined to mold her into the obedient daughter her willful young mother refused to be. In reaction, Harrison’s rebellious streak turned silently inward, toward anorexia, self-mutilation, and an obsession with death and physical vulnerability that is with her even now, as we discover in the droll but unsettling account of her campaign to assassinate a tick that had dared to attach itself to her daughter, and in her morbid fascination with relics of the deceased.

Her affecting, beautifully crafted autobiographical meditations read like therapy by other means – successful, we hope, for the sake of the children.

—————————-

ANNE CHISHOLM for THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

A painful childhood is usually a rich seam for writers. Kathryn Harrison is a beautiful blonde American novelist in her forties whose first autobiographical book, The Kiss, was a finely written and widely acclaimed account of her seduction by her father. Now, in this short memoir made up of loosely connected essays on childhood, her own and her daughter’s, she describes with the same alarmingly graceful lucidity how she survived her mother’s emotional neglect.

As a baby, Harrison was handed over by her teenage mother to be brought up by her grandparents; she seldom saw her father, who plays no part in this book. Her eccentric grandmother was British, but had grown up in Shanghai before settling in California; she was a rich source of exotic, romantic stories. Harrison loved her grandparents, but grew up craving her dashing, elegant young mother’s love and attention, aware that somehow her very existence was an encumbrance.

When she was six, she was taken to a Christian Science healer after she had split her chin open in a car accident. Under the woman’s hands she felt a blissful sense of transcendence and freedom from pain and fear. This rapture, which as the book’s title indicates she has never stopped pursuing, showed her, she writes, “that spirit could overcome matter . . . that I could overcome myself”.

For all her determination to escape the physical, Harrison was, and remains, obsessed with mortality and the dramas of the body. She spares the reader little, writing in grisly detail about her mother’s death from cancer, the removal and dismemberment of a fat blood-gorged tick from her daughter’s scalp, her clumsy attempt to assist a cat with the birth of a deformed kitten and her own prolonged labour when her third child was born.

One entire chapter of the book describes the visit of professional head-

louse removers to the Harrison family. It is a measure of her considerable power as a writer that this minor event takes on the solemn significance of a religious rite.

Gradually Harrison’s purpose becomes clear. By writing in such unflinching detail about her own and her children’s bodies, she is exorcising her old fears and celebrating the physicality of maternal love. In the end, her passionate feelings for her children lead her to pity and forgive her mother’s inadequacies. This book is unnerving to read, driven as it is by naked emotional need; but Harrison’s intelligence and honesty make it worth the effort – just about.

———————————

JULIE MYERSON, for THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

Kathryn Harrison has written some of the most daringly, darkly uncompromising books I’ve read. She explores love, sex, death and their shattering legacies of hate and pain with an honesty that occasionally borders on the masochistic. She’s good on physical tenderness – and never more memorably than in her last novel, The Seal Wife – but still a terrifying sense of sensual and emotional isolation seems to linger. Self-disgust, the fastidious impulse to hide or wash or sweep clean – these surface again and again in her writing. Why? Where on earth does it come from? Her unswervingly honest memoir may not offer easy answers to these questions, but it’s pretty revealing about some of the impulses that feed her work.

It is less a memoir, actually, than a series of apparently haphazard recollections and responses. The binding theme is motherhood: the furious, sometimes devastating power each female generation wields over the next. Harrison was born out of wedlock to an 18-year-old – “I was my mother’s disgrace.” When she was six, she was handed over to her grandmother as the “hostage” the mother imagined would “buy her freedom”. That freedom was duly attained, but at a cost. The love-struggle between Harrison and her glamorous, errant mother grimly continued until the latter’s death from breast cancer two decades later.

Unsurprisingly, Harrison’s craving for maternal love only intensified with the years. More than anything, she desired that physical presence, that approval. And when it wasn’t forthcoming, she discovered plenty of ways to punish herself, including anorexia and shoplifting. None made any difference: “she didn’t care that I shoplifted; she thought it was funny”.

Meanwhile, Harrison’s grandmother was a fantastically, eccentrically amoral character – “even if I didn’t articulate it to myself, I recognised danger at the hands of someone as potentially ruthless”. There’s plenty of black comedy: the rug on the slippery hall floor, for instance, that tripped up every visitor but was never removed – “she was kind to the victims, offering ice wrapped in a towel, ginger ale, cups of tea”. And there are the shreds of raw meat stuck to the walls and doorframes, because the grandmother regularly chopped offal for her 17 cats and neglected to wash her hands properly.

But the abiding flavour is of chaos and pain. Harrison recognises that she and her grandmother mirror each other with their furious passions, their relentless, almost impatient need to test, consume, devour the things they love. “She loved Chanel No 5, she loved dark red, she loved steak and Lindt bittersweet chocolate… when she bought another kind of chocolate, it was only to make sure that it was less desirable.”

It would be comforting to be able to say that Harrison grew up to be a stable, happy person, a successful writer married to another (her husband, Colin, is also a novelist) who lived happily ever after with their three children. Some of that, I’m sure, is true. But the episodes she offers from her life today aren’t reassuring. They reveal a woman teetering always on the brink of terror, obsession and overreaction.

Finding a tick in her daughter’s hair, she spends a terrified, stricken day trying to decide what sort of death it deserves. Colin calls her from work: ” ‘How’s it going? You working on your book?’ ‘Fine,’ I say, ‘Yes,’ I lie.” Discovering her children have headlice, she finds herself similarly disgusted and terrified, and panics, suffers nightmares: “together my children and I are falling down a long chute, like a laundry chute, at the bottom of which is a vat of something that’s supposed to cure lice, except it doesn’t . . .” Finally Harrison calls in the serious headlice-busters and pays a fortune to have them apply chemicals to every head in the family. It’s a very funny episode, but it also leaves a bewildering taste in the mouth. They’re only headlice, for God’s sake, you want to whisper in her ear.

Also bewildering is everything that’s missing. No one who has read Harrison’s earlier memoir The Kiss will be able to forget that these same teenage years were overshadowed by an intensely shocking incestuous relationship with her estranged father. But that’s just not here. Though the author has every right not to go there again in print, it’s hard not to see it as the missing piece of the emotional jigsaw.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/arts/openbook/openbook_20030330.shtml