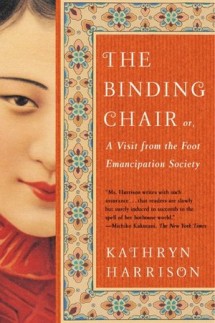

ABOUT THE BOOK

As the 19th century waned, China began to buck Western Imperialism, Russia was experiencing a revolution, and the nations of the world inched toward the first global war. With these epic events as the boisterous backdrop, Kathryn Harrison has crafted an ironic, lyrical, shocking novel about the secret lives of women, the universal search for home, and ultimately, the power we have to direct the course of our own lives-and the lives of those we love.

The center of The Binding Chair is May Li-an upper class Chinese woman who, as a child, was subjected to the ancient ritual of foot binding. Exotic and beautiful, complex and compelling, May Li’s childhood was consumed with preparations for marriage. May accepted its inevitability, even indulging in romantic fantasies about her potential mate. But when the rich silk merchant to whom she was delivered turned out to be a sadist, May breaks free from her husband’s house, goes to Shanghai, changes her name, supports herself as a prostitute, and masters the English language.

May has a plan: to land a wealthy English husband, procuring for herself security, love, and an escape from her Chinese heritage. Opportunity arrives in the unlikely form of Arthur Cohen, the Jewish philanthropic brother-in-law of a wealthy businessman. Arthur goes to the brothel with a specific purpose-to emancipate a victim of foot binding. Instead, he is utterly captivated by May’s tiny, fleshy appendages and marries her.

May’s affect on the Cohen family is hypnotic and total. Arthur’s niece, Alice, fixates on her mysterious opium-smoking aunt. Dolly, her high-strung mother, attempts to squelch their relationship by sending Alice to boarding school in England. The separation only intensifies Alice and May’s connection. Alice crusades to fix May’s crippled feet. May crusades to prevent Alice from becoming trapped by the passion that so often ensnares the young. May, Alice finds, revels in hobbling around on her deformed feet. In turn, Alice is enthralled by the rush of her own life, of new love, of the exotic. Alice’s and May’s stories are brilliant counterpoints to one another, illustrating that while two individuals may be born in a different time and place, the profound questions that compel them to spend their lives searching for answers are universal.

PRAISE

“The Binding Chair is a resonant, elaborately constructed novel, rich in incident, bustlingly peopled, often surprisingly funny. It is also a heartening sign of literary risk-taking.”–New York Times Book Review

“[A] deeply humane novel.”–Wall Street Journal

“This is her best work to date, an intricately and elegantly constructed narrative about intersections of character and fate, history and chance, and the ironic, tragic fulfillment of hearts’ desires.”–Publishers Weekly

“Ms. Harrison writes with such assurance…that readers are slowly but surely induced to succumb to the spell of her hot house world.”–Michiko Kakutani, New York Times

“Inventive, provocative, and entertaining.”–Booklist

Harrison renders historical settings with textured fidelity. Here she spins an exotic and irresistible tale set mainly in Shanghai at the turn of the last century, with evocative side trips through Russia, England and the French Riviera. The changing culture of China is reflected in the life of a compelling character. Born in 1884, May must submit to foot binding as a child, and thereafter endures constant pain and the constriction of her freedom. Despite her deformed feet, at 14 she escapes a sadistic husband and pursues a new life in a brothel in Shanghai, where she eventually marries a kindhearted Jewish immigrant from Australia who’s a member of the Foot Emancipation Society. May’s stubborn, indomitable spirit isn’t hampered by her husband’s inability to find a job, since they live in the opulent household of his sister and her husband, and their two daughters–the younger of whom comes under May’s thrall. Manipulative and autocratic, May spends her life despising her useless feet, fighting convention and adoring her high-spirited niece. But she cannot escape the ancient legends and superstitions that shadow her life, or the opium habit she develops after several emotional blows. Lost children are one theme here, and the varied ways people deal with such loss. Another is the lot of women striving to be independent in a hostile world. Harrison describes in harrowing detail the barbaric foot-binding ritual, various forms of sexual brutality, parental abuse and official torture. She is equally deft at social comedy, erotic titillation and tender sentiment. This is her best work to date, an intricately and elegantly constructed narrative about intersections of character and fate, history and chance, and the ironic, tragic fulfillment of hearts’ desires. -Publishers Weekly

One of the women in Kathryn Harrison’s The Binding Chair has a mind “which had always suffered from morbid imaginings.” Harrison could be telling a gentle joke on herself here, for she has stuffed her novel with such imaginings. Here are broken fingers, abortions, Marathon Man-style dentistry, sodomy (not in a good way), and even an abused chicken. One particular morbidity, though, is the spur of the tale.

May, a young Chinese woman, suffers the brutal ritual of foot binding at the turn of the last century. The book follows May from a bad marriage (think Raise the Red Lantern) to Shanghai, “the infamous city of danger and opportunity.” May–either despite or because of her foot’s deformity–is considered a woman of astonishing beauty. “Each part of May, her cuticles and wrist bones and earlobes, the blue-white luminous hollow between her clavicles, inspired the same conclusion: that to assemble her had required more than the usual workaday genius of biology.” Her beauty, her fetishistically bound feet, and her quick mastery of a handful of languages earn her a pile of money and finally a Western husband.

May develops a close relationship with her husband’s Jewish family, especially with her unruly niece Alice. Harrison’s scrupulously researched novel follows the two of them from Shanghai to London and back again, encountering along the way a colorful cast of women who’ve all suffered a disfigurement, mental or physical, that echoes May’s. Finally several of the women come together in Nice, where each works out her destiny. The Binding Chair is far-flung, geographically and emotionally, and never quite coalesces, but perhaps the author was intentionally seeking to make a story about the Chinese and the Jews that has a feeling of diaspora. You’ve got to hand it to Harrison. Most writers, upon developing a fascination with Shanghai, would write a nice article for Travel & Leisure and have done with it. Kathryn Harrison has forged an ambitious novel. –Claire Dederer

“Harrison is known best for her galvanizing memoir of incest, The Kiss (1997), but she is also a novelist of sure powers with a taste for the erotic, the taboo, and the macabre. Her latest novel spans the life of a beautiful, upper-class Chinese woman who is subjected to the ancient and brutal tradition of footbinding in the waning years of the nineteenth century. May’s entire crippled youth is dedicated to preparing for marriage, but when her husband turns out to be a sadist, she runs away to Shanghai and enters a brothel. She not only becomes sexually adept, she also teaches herself English and French, hoping to be rescued by a smitten foreigner. Her knight does appear, albeit in the unlikely form of Arthur Cohen, a red-haired, softhearted Jewish idealist, who lives with his high-strung sister, Dolly, her wealthy and generous husband, and their two daughters, Alice and Cecily. Arthur is involved in a campaign against footbinding, but rather than being repulsed by May’s misshapen feet, her painful claws of flesh, he is enthralled and ends up marrying her. Glamorous May joins the Cohen household and finds a kindred spirit in Alice, a renegade destined for trouble. Dolly attempts to minimize what she perceives as May’s corrupting influence by sending the girls to a British boarding school, a plot twist that enables Harrison to set some of the novel’s most intriguing scenes aboard the then brand-new Trans-Siberian Express and add melancholy Russians to her vibrant and enticing cast. Her plot–sinuous, surprising, and rife with crises both ironic and tragic–is compelling, too, although she fails to fully address the questions of fate raised by May’s suffering. Even so, Harrison is inventive, provocative, and entertaining. — Donna Seaman, Booklist

“An engrossing tale contrasting the lives of a young Caucasian and her Chinese step aunt. Harrison is a powerful, hypnotic writer fascinated by the psychosexual elements of a secretive human life. Her latest effort is skilled in incorporating themes from her earlier fiction and from her life as well, it would seem, as revealed in The Kiss (1997), the memoir of her consensual sexual relationship with her father. Like Poison (1995), this novel is set in a historical period (the first half of the 20th century) and an exotic locale (Shanghai), and, like all of Harrison’s books (Exposure, 1993, etc.), it examines how women get and use sexual and social power. The first of the two contrasting but intertwined stories focuses on May, a Chinese-born woman whose traditional foot-binding ceremony is recalled in vivid and horrifying detail. The second follows Mays step-niece, Alice, through adolescent sexual awakening. While both are strong, forceful women who clash accordingly Mays life makes for the more compelling drama. Addicted to opium for years, and hobbled by the foot-binding, she is a fierce character who never becomes a clicheed dragon lady. Particularly gripping are the portrayals of her abusive first marriage and of her convention-defying second try with Alice’s uncle Arthur. Harrison deals subtly with the themes of racism and anti-Semitism (Arthur’s and Alice’s families are Jewish) even when constructing so obvious a set-piece as the scene in which May is arrested at London’s Fortnum & Mason for using slaves to carry her around. In a book distinguished by atmospheric backdrops and panoramic scope, two additional pleasures stand out: an abundance of full-bodied minor characters, and a sharply telling portrait of expatriate Westerners getting rich in the East. A deft weaving together of sexuality and the macabre into a rich fictional tapestry.”–Kirkus

BOOKS OF THE TIMES: Willful Sensation Yet Not Soap Opera

By MICHIKO KAKUTANI

Though Kathryn Harrison’s new novel, ”The Binding Chair,” takes place not in contemporary America but in turn-of-the-century Shanghai, the book recapitulates many of the themes of her controversial 1997 memoir, ”The Kiss.” In this case, foot binding, the old Chinese custom of mutilating the feet of aristocratic girls, is a kind of metaphor for the child abuse and incest chronicled by Ms. Harrison in that earlier book — a metaphor for the sort of childhood trauma that persists throughout an individual’s life, warping emotional reflexes and leaving behind a permanent sense of otherness and alienation.

The smell of incense and opium wafts lugubriously through the pages of ”The Binding Chair,” creating the heavy, sensual atmosphere of an old-fashioned Gothic. Ms. Harrison not only dwells on the painful ritual of foot binding with almost voyeuristic fascination, but she also resorts to contrived plot high jinks and willfully sensational set pieces to move her story along. By book’s end, the corpses have piled up with alarming speed: three people die by drowning, two by fire, one by torture and countless others from an epidemic.

And yet for all these melodramatic excesses, ”The Binding Chair” never devolves into simple soap opera. Ms. Harrison writes with such assurance, such matter-of-fact sympathy for her characters, that readers are slowly but surely induced to succumb to the spell of her hothouse world.

As in her last historical novel, ”Poison” (1995), Ms. Harrison tells the overlapping stories of two women whose lives mirror and counterpoint each other’s. The first woman, May, was born to privilege and wealth, and her feet were painfully bound when she was 5. After a nightmarish marriage to a sadistic man, May runs away to Shanghai, where she spends seven years working in a brothel. There she meets the man she will marry, a good-natured do-gooder named Arthur Cohen who invites her into the fold of his expatriate family.

Just as he believes that his quixotic plans for reform (registering prostitutes, regulating surgery and inveighing against pornography) can transform Shanghai into a more humane city, so Arthur believes that he can save May from her past. After their only child, Rose, dies in a boating accident, however, May slips further into her opium habit, escaping into a dream world where memory can be blurred if not erased.

The second woman to hold center stage in Ms. Harrison’s novel is May’s niece, Alice Benjamin, the daughter of Arthur’s high-strung sister. Alice is a bright, rebellious girl who shares her aunt’s defiance of authority: she gets herself expelled from boarding school and allows herself to be abducted from a train by a Russian Army engineer. May sees Alice as a substitute for her lost daughter and tries to adopt Alice as her own, an act that ultimately estranges the two women.

Cutting back and forth between Alice’s story and May’s, Ms. Harrison conjures up the vanished world of early-20th-century Shanghai, a world in which women are brought up to please and service men, a world in which class and sex determine one’s fate. Although May tries to escape her destiny and though she eventually flees to the south of France with Arthur’s family, her damaged feet are a constant reminder that she comes ”from another world.” She is scornful of Alice’s efforts to get her medical help, impatient with others’ efforts to make her fit in. Her one passion becomes swimming — an activity where she can ”move unhindered by her feet,” travel ”without help, as fast and as gracefully as any other person.”

Among the people Alice and May cross paths with are a motley assortment of eccentrics, misfits and fellow outsiders. There’s Captain Litovsky, the Russian engineer who tries to kidnap Alice during a long train trip across Siberia. There’s Suzanne Petrovna, a penniless translator and editor who flees to the south of France to escape her abusive father. And there’s Eleanor Clusburtson, a former math teacher whose mishap with a false tooth unexpectedly helps Alice’s father corner the lucrative Chinese rubber market.

Though Ms. Harrison’s orchestration of these people’s intersecting lives is clumsily stage-managed, her evocation of May’s life is persuasive enough to make the reader overlook such missteps. Indeed, ”The Binding Chair” ratifies the notion that a gifted writer can take seemingly lurid subject matter and a tricked-up plot and transform them through emotional insight and plain old storytelling verve into an involving work of fiction.

———————————————

THE BINDING CHAIR: Or, A Visit From the Foot Emancipation Society.

KATHRYN HARRISON is best known for her controversial 1997 memoir, ”The Kiss,” an account of her incestuous relationship with her father. A best seller, it provoked widespread debate about the role of the public confessional in our scandal-hungry society. Yet in the course of these discussions, the literary merits of Harrison’s enterprise were rarely at issue; the book’s content, which catapulted her name to prominence, was — at least to this reader — a distraction from Harrison’s considerable writerly gifts. The revelation of sensational facts seems all too easy when compared with the challenge of creating subtle fictions.

Prior to ”The Kiss,” Harrison wrote three powerful and ambitious novels that amply demonstrate both her meticulous style and her imaginative range. In them she roamed with equal ease from the grit of contemporary New York to the machinations of the 17th-century Spanish court. It is, then, a pleasure to see her return to her fictional calling.

”The Binding Chair” is a resonant, elaborately constructed novel, rich in incident, bustlingly peopled, often surprisingly funny. It is also a heartening sign of literary risk-taking. Set over four decades, from the late 19th century until the period between the two world wars, traveling from China to Britain and the south of France, Harrison’s book tells the stories of two women, May Cohen, the beautiful Chinese wife of an ineffectual but well-connected Australian, and her niece, Alice Benjamin, each of whom struggles, in her own vibrant but doomed way, to be free of what Alice thinks of as (but doesn’t actually call) ”crippling rules.”

The crippling of May is literal. When she is a little girl of 5 (then named Chao-tsing), her feet are bent within tight cloth bandages by her grandmother, who assures her: ”When you are grown, you will be very beautiful. Your feet will be the smallest and the most perfectly formed lotuses. Your walk will be the walk of beauty, and we will tell your suitors that you never cried out when your feet were bound.” The deformity to which May is then subject — and its agony — lurks at her heart. ”It was, May knew, her feet that held her between one world and the next. On her red shoes, she balanced between East and West, China and Europe, misery, happiness.” Crippled, she is hardened; she becomes a woman of absolute determination and resilience, a magnificent monster.

Alice, the younger daughter of May’s husband’s sister, is May’s favorite, her surrogate child. (Fate and May’s own ambition have taken two natural daughters from her, two tragic stories that emerge in the course of the novel.) We learn from the outset that Alice has been ”separated from May only once, in 1913, when she was 12 years old,” after her parents, expatriates in Shanghai, discovered her rolling opium balls for her aunt and packed her off on an ill-fated expedition to boarding school in England. Other sections of the novel, set in Nice in the 1920’s, chart a different and more enduring form of separation. Now an adult, Alice falls in love with a Russian named Evlanoff, and in so doing irretrievably betrays her aunt.

It is a betrayal whose seed is sown in that first departure: in the course of her long train ride across Russia to Europe with her sister, Cecily, their histrionic mother and small retinue, Alice becomes the obsession of a deluded Russian army captain named Litovsky, who imagines that she is his own dead daughter and attempts to abduct her. The unanswered question of why Alice willingly follows him off the train remains the hidden key to her youthful personality; it is a question posed again by Evlanoff, even as her surrender to him re-enacts that childhood scene.

On that same fateful trans-Siberian train trip lurks another woman who will resurface in Nice many years later and become part of the Benjamin-Cohen family: a bereaved and isolated spinster named Suzanne Petrovna. And in the course of the girls’ short but colorful stay in London at Miss Robeson’s Academy for Young Ladies, Alice befriends a brilliant but unappreciated young math teacher named Eleanor Clusburtson — crippled, in her turn, by a terrible lisp — who returns with the girls to Shanghai and uses her talent to make their father a fortune. (It is worth noting that the family’s escapades in London, including May’s disastrous visit to Fortnum & Mason in an improvised sedan chair, constitute, along with Miss Clusburtson’s unfortunate history, a triumph of black comedy.)

Harrison intersperses the story of Alice’s youth with the even more dramatic account of May’s struggles — of her father’s death when she is 12, of her early betrothal and miserable marriage, of her escape to Shanghai and her life in a brothel until she is rescued and married by Alice’s uncle, the hapless Arthur Cohen, whose first visit to May is in his capacity as a member of the Foot Emancipation Society.

Throughout the novel, Harrison is particularly adept at capturing the subtleties and perversities of desire, noting, for example, that Arthur’s passion for May is focused upon the very feet he thought to have liberated: ”The tiny foot in his hand shape-shifted. One minute it repelled him, the next it seemed suddenly to express the beauty of the whole female body. Wasn’t it all there, in May’s foot? The smooth white of her neck, the curve of her breast and hip, the crook of her smallest finger, the delicate, mauve folds of her most intimate places.”

The family’s life in Shanghai during World War I and after is marked by disintegration and disaster: the influenza epidemic takes its toll, as does, more severely, the madness of Alice and Cecily’s mother, Dolly, who inadvertently burns down their house, killing both herself and her brother. Her survivors eventually move to Nice, but the girls’ father, Dick Benjamin, as well as Miss Clusburtson and Cecily, fades almost entirely from view.

In the sections set in France, the richness of incident in the women’s earlier lives is diminished. Alice retreats to Evlanoff and to sex — scenes that provide the main characterization of her as an adult and fail, therefore, to characterize her at all. May, having attempted to shake off depression by decorating their new home, adopts a host of charity cases — the lonely Suzanne Petrovna most important among them, as she is taken into May’s bed. And, crucially, the Chinese woman who can barely walk learns to swim. Alice notes early in the novel that ”May didn’t do things casually. She wouldn’t pursue swimming for the pleasure of it. . . . She must have some sort of a . . . a plan.” Meanwhile, Alice persistently attempts to help May with her feet, dragging her against her will to a fitting for orthopedic shoes. The Foot Emancipation Society pursues May, in some form or another, to the very end.

”The Binding Chair” is an intricately patterned novel. In its sidelong anecdotes and minor characters as much as in its central ones, it explores the theme of brutality against women, of their crippling. (This is traced in all its metaphorical possibilities and illuminates the way that women, as much as and sometimes more than men, are culpable.) The novel also evokes women’s ”dis-ease” and the polymorphous perversities of desire. Harrison’s vision is bold and unsparing, portraying a world in which a woman’s survival comes at a terrible cost, a world in which people are doomed to isolation, abandoned by all but the weaklings they can control. The novel continually surprises. Its narrative turns and its tonal shifts — from the rhythms of the epic to those of the erotic, with pauses for comedy along the way — are as deft as they are unexpected.

Ultimately, though, ”The Binding Chair” is a novel whose ambition outstrips its achievement. For all its impressive vitality, it reveals little of the interior depths of its characters. And lacking this, it ultimately lacks a heart. Neither Alice nor May lives beyond or behind her actions, and the elaborate structure Harrison has built for the telling of their stories seems designed more for a clinical juxtaposition of their trajectories than for a sustained exploration of their essences as complex individuals.

Only in May’s terrible but somehow beautiful end — in which she shows herself monstrous to the last and yet magnificent, and as a consequence utterly human — does Harrison allow us a glimpse of this woman’s carefully guarded soul. These few haunting pages are the novel’s highlight, more moving than anything that has come before. —Claire Messud, The New York Times Book Review

READER’S GUIDE

1. Discuss May’s relationship to the foot binding ritual. Did you perceive her as being a victim? Do you think that May thought of herself as a victim? Why or why not?

2. If you could identify one event as being the one that influenced the path that May’s life took, what would it be?

3. How did the third person narrative affect the tone of the novel? How would it have been different if the reader had seen the world specifically through May’s eyes, or even Alice’s?

4. Was Dolly’s impulse to separate May and Alice well founded, or was she being hyper-vigilant? Would you characterize May and Alice’s connection as a healthy one?

5. If May’s feet had not been bound, would Arthur have loved May? If not, does that diminish his love for her? Do you think that May was in love with Arthur, or do you think she needed him?

6. Why didn’t May want to wear the orthopedic shoes?

7. The Binding Chair teems with characters, and all of them are somehow connected to each other. How did this support the themes in the novel?

8. Was the conclusion of the novel satisfying? Why or why not?

INTERVIEW, BOOKREPORTER.COM

September 29, 2000

Novelist and author of one of the most controversial memoirs, THE KISS, Kathryn Harrison discusses her new novel THE BINDING CHAIR — a book that spans continents and cultures — her interest in taboos, and much more in this interview. Bookreporter.com Writer Jana Siciliano dove into Harrison’s work headfirst, reading her memoir, her latest book, and POISON. Don’t miss this conversation with a writer who writes with strength and an addictively poisonous pen.

BRC: Your most recent novel, THE BINDING CHAIR, is subtitled A VISIT FROM THE FOOT EMANCIPATION SOCIETY. Would you please tell us a little bit about that and how you came across this idea of the society?

KH: While doing research on footbinding in Chinese history I came across the “Natural Foot Society,” founded by western missionaries during the end of the 19th century and dedicated to raising the consciousness of Chinese women — so that they would resist binding their daughters’ feet. My fictional society is very loosely based on the historical one.

BRC: Why is May, who can barely walk because of her tightly bound feet, learning to swim in the beginning of the book? It’s a strange and dreamlike sort of way to begin her story. Tell us why you chose to open it up that way.

KH: May is an independent woman who feels compromised by having to rely on other people to transport her. Swimming is the one means of travel that she can accomplish on her own, and thus it becomes very important to her. And, as we see by the end of the book, her swimming lessons are a fated apprenticeship. Themes of water and swimming, and drowning, occur throughout the book — it’s the novel’s central image, aside from the bound feet, and connected with the feet.

BRC: The brunt of THE BINDING CHAIR follows May through her first damaging marriage and then her remarriage to Westerner Arthur Cohen — all the while it also follows the life of her young step-niece, Alice, who is going through troubles of her own. What do you think the two very different women have in common, if anything?

KH: They’re both strong willed, and intent on whatever freedom they can find. I wanted to explore a surrogate-mother relationship, how it might unfold, the effects on either character. I think of May as the central character of the novel, and Alice as the supporting role, the person through whom we experience May. Alice is infatuated, then disenchanted, then resigned to a more complicated vision of her aunt; and, through her, the reader is lead on a similar journey.

BRC: Another one of your novels, POISON, has a subplot that centers around the love between a poor girl and a Catholic priest. What led you to write about this taboo relationship?

KH: I’m interested in taboos, who breaks them and how, and what the cost is. On a personal level, the relationship between a girl and a priest was one that allowed me to explore my relationship with my father, a kind of prelude to the material I dealt with in THE KISS.

BRC: Other reviewers note your novels’ prevalence for the taboo, erotic, and sometimes gruesome. What inspires you to delve into these themes?

KH: It’s not a choice — like any other writer, I’m driven to examine those things I need to understand.

BRC: What is it about the theme of liberation and freedom that compels you to base story after story around it?

KH: Freedom, exile, entrapment — all obsess me. If I could tell you why, then their power would have ceased.

BRC: You often write books, like POISON and THE BINDING CHAIR, that require intensive historical research. How do you do it and why does a non-contemporary framework interest you as a storyteller?

KH: Historical novels aren’t history any more than novels set in the future are accurate predictions — it’s just a way of projecting contemporary concerns onto another screen. I get sick of my own context and like to explore other ones. I do research in libraries, through interviews, and through travel.

BRC: Do you feel that it is important for writers to explore their own psyches in their work or is it easier and perhaps more commercially viable to just make stuff up?

KH: I think writers write the books they write, the ones that are true to themselves. They’re far less calculating than readers might imagine. I can’t comment on what’s easier or more commercially viable — I write what I’m invested in writing, psychically invested. I couldn’t do it any other way.

BRC: Your husband is the author Colin Harrison. What is the most difficult part about being a writer married to another writer? What is the greatest benefit of sharing a home with another writer?

KH: Colin and I met as writers, so it’s always been the status quo, and we’ve always been more aware of benefits than difficulties — there’s a lot we never have to explain to each other.

BRC: When did you decide to be a writer?

KH: In my early twenties.

BRC: What contemporary writers do you admire? Has any one of them affected the way you write?

KH: I just read DISGRACE, by Coetzee, and admired it greatly. I like Martin Amis, Margaret Atwood, Flannery O’Connor. Faulkner. MADAME BOVARY is my favorite novel. Not exactly contemporary, but I can’t think of a book that comes close to its achievement. I don’t know what influences me — everything and nothing.

BRC: How do you see the Internet affecting the future of fiction?

KH: I don’t much, at least not the kind of fiction I care about.

BRC: Some authors are willing to publish stories or entire novels online as eBooks. Would you ever consider this?

KH: Ever — I don’t know. Now, no.

BRC: Do you believe that art can change the world, especially the art of literature and the sharing of one’s personal history?

KH: I think art is what makes life bearable, both as an audience and as a writer.

BRC: What one sentence of advice would you give to aspiring writers?

KH: Revise.

© Copyright 1996-2005, Bookreporter.com. All rights reserved.

INTERVIEW#2

Q: What lead you to write a novel about this particular facet of China’s cultural history-foot-binding?

A: My mother’s mother, who raised me, grew up in China at the turn of the last century, so the time and place has always occupied a large part of my imagination.

Q: How did you research this topic? Were you able to get first-hand accounts from women who participated in the ritual of foot binding?

A: Much of what I know of China comes from my grandmother-a vast untidy anecdotal history. To supplement this I did a lot of research in libraries, including oral histories taken from Chinese women whose feet were bound, and I traveled to Shanghai.

Q: How did you envision the narrator? As a woman or a man? Would you have been able to write this novel in the 1st person?

A: It’s an omniscient narrator, but I would describe the consciousness of the book as female. Had it been first person then it would have been May’s narration, and I didn’t want to write it from inside her perspective because it would have made her less mysterious. Ultimately I wanted her, and her suffering, to be unknowable.

Q: Do you think that Western society is too moralistic and simplistic in its assessment of other culture’s customs? In your mind, were Chinese women victims of this custom, or was their relationship to it more complicated than that?

A: Yes, westerners are very reductive and chauvinistic in their approach to other cultures. As evidenced by the fact that Chinese women bound the feet of their daughters and were reluctant to let go of the power the bound foot conveyed, the relationship was not one of simple victimization. I wanted to write about the use of disfigurement, both on a physical and spiritual level, by the disfigured: May.

Q: Are you working on a new project?

A: I’m just finishing up the first draft of a novel set in Alaska, around 1915

————————

Bound, Not Gagged

Kathryn Harrison Speaks Out About Public Scorn, Private Obsessions, and Her New Novel

by Joy Press

May 17 – 23, 2000

Kathryn Harrison may present a portrait of perfection, but the byproducts of her vida loca surface in conversation.

Kathryn Harrison knows what it feels like to cross the line. After the publication of her memoir The Kiss, she went from being a writer of well-reviewed midlist literary fiction to a public pariah. She became chief scapegoat of a culture of confession run amok, the highbrow spawn of Jerry Springer. The central disclosure of The Kiss, that at age 20 she had an incestuous affair with her father, whom she hadn’t seen since infancy, unleashed a media juggernaut that could have permanently derailed Harrison’s career, not to mention her life.

But three years later, Harrison is the picture of serenity. Ensconced in the parlor of her giant Victorian house, Harrison exudes a cool confidence. She’s recently given birth to her third child, and she is not only on her feet but giving an interview with baby Julia glued to her breast as the dog begs to be fed and the doorbell rings. Her air of efficiency suggests a certain creative overcompensation: Having spent a less than average childhood in a not-quite-nuclear family (raised by Grandma, illicit romance with Dad), she has surrounded herself with the trappings of domesticity. Harrison sees stability, or at least the veneer of stability, as part of her job as a parent. She explains sensibly: “If I just lay down in the tracks like I sometimes sort of feel like doing, the children would be wildly anxious and resentful. You have to keep all the balls in the air and manage everybody’s needs.”

She may present a portrait of Park Slope perfection, but the fascinations that are byproducts of her vida loca surface in conversation. She’s a Cronenberg fan and an aficionado of old medical books (“things like leeching”) and it seeps into her work. In the 1993 novel Exposure, the central character is a self-cutter; 1995’s Poison bubbles with blood; and her latest novel, The Binding Chair, or A Visit From the Foot Emancipation Society (Random House), revolves around foot binding, a Chinese ritual in which young women’s feet were bound and mutilated to make them erotically appealing to men.

Harrison attributes her fixation on all things bloody to a car accident at age five. “My grandfather was driving me to school and wrecked the car,” she says. “My mother had moved out maybe six months before and I was completely bereft. I cracked my jawbone and there was blood all over my face, and my mother just materialized. She had been driving to work, saw the car, and pulled over. I began to bleed, and my mother, who had disappeared, reappeared!” Foot binding, she says, is connected to the blood lust: “It’s bandaging, it’s about destroying or compromising the flesh.”

The Binding Chair started out as the story of Harrison’s grandmother, who grew up in Shanghai. Because her grandmother died some years ago, Harrison turned to historical research to fill in the gaps. “I came across this old text on the erotic pleasures of the bound foot, and it insinuated itself into my head in a way that was impossible to resist. It was a readily exploitable metaphor because everyone in the book connects to each other based on their particular damage.”

The book’s heroine, May, is a brazen, modern character — imagine a crippled, Chinese Courtney Love. She evades her fate by escaping from the house of her cruel first husband on the back of a servant and becoming a prostitute. One of May’s clients is her future husband Arthur, a member of the Foot Emancipation Society (an antifootbinding group), who finds himself in the grip of his own perversity: “The last loop of cloth fell away from May’s foot and revealed a warm claw of flesh, luminous and slick and folded in upon itself. It wriggled slightly, and he let it go, then grasped it again. . . . Arthur’s head felt hot inside. The thought sickened him, but he wanted to take the misshapen foot in his mouth. To swallow it, her, whole.”

In all of Harrison’s novels (and of course in The Kiss), damaged female characters abound. But May’s ailment is unusually overt, she is a woman effectively castrated by the male world, a female eunuch. Her drama sometimes feels schematic, like a scenic detour into Women’s Studies 101, in which a forgotten woman’s history is disinterred and dissected.

Harrison admits to an exhibitionist streak: of her five books, two are semiautobiographical novels and one is a soul-scraping memoir, but sees fiction writing as a more subtle process than just oozing onto a page. “May isn’t me, but when you write a novel you tend to fracture yourself into various bits and use them. She’s vulnerable and damaged and she’s not going to let anybody know that. And she’s manipulative. She’s probably an amalgam of aspects of my personality and my grandmother’s. My grandmother was very manipulative. . . . Even if we weren’t talking I felt this great sucking presence from the other side of the couch! My mother became an incredibly defensive person who was hidden inside a psychic fortress to keep herself safe from her mother. And I grew up with that same woman.”

A lot of writers veer away from making connections between their life and art. But Harrison’s childhood seems like her touchstone: All roads lead back to the family romance, so to speak. At one point in our conversation, Harrison mentions that she’s always been terrified of twins, a fear stemming from her problem with personal boundaries, and goes on to disclose one of her very first memories. “I remember my mother and my grandmother fighting, and my consciously drawing a magic line: This is you, this isn’t me, this is me, this is not you,” she says, mechanically drawing borderlines in the air.

One of her critics’ prime accusations is that Harrison blurs the line between fiction and nonfiction too much: Thicker Than Water, Harrison’s first novel, was about a girl sexually abused by her father, and the second, Exposure, was about a woman whose father photographed her naked. When The Kiss came out, many complained that Harrison’s novels were just thin variations on her life story. Which they were, albeit well-written ones. But because of the charged nature of Harrison’s experience, one can’t help but see her as a woman returning obsessively to some primal scene, picking at scabs.

Harrison says now that if she’d written Thicker Than Water “10 years down the line when people were writing more confessional books, maybe I wouldn’t have written it as a novel.” She came to dislike it “for the ways in which it had cloaked my experience. Isabel, the narrator of that novel, is a more innocent version of myself, more of a victim than I was. The father is more of a prosaic bad guy than I understood my own father to be.” That sense of self-betrayal, she says, was the impetus for writing her memoir.

But Harrison got caught in the backlash against confession, and The Kiss served perfectly as a target. “I expected that a number of people would come down on me for what I had done: Kathryn Harrison is a reprehensible person, she is amoral. I didn’t expect to be attacked for having chosen to write about it,” she says, seeming genuinely puzzled. “And I was foolish enough to believe that people could say, ‘This is a distasteful subject, but at least the book is well-written.’ ”

She was accused of a exhibitionism and a naivete about sexual abuse. Most of all, critics were angry that she published the thing with her father (not to mention her children and her husband, Harper’s editor Colin Harrison) still living. “People said, ‘Write it, but put it in a drawer.’ If I had been planning to put it in a drawer, there would have been a lower standard imposed on the book, in terms of honesty, every single thing I wrote I had to stand behind.”

A part of Harrison obviously revels in her role as provacateur. The media onslaught “was exhausting,” she says, “but I have no regrets about publishing the book. It was a real lesson in projection. I was in a position to have people explode in my face! I would just stand back and say, ‘Whoa! What is going on with you?’ It was as if the book had this mechanism for lancing boils!

“People really don’t like gray areas,” she smiles. “I looked at my father, mother, and myself as human beings . . . who made a big mistake. We fucked up! But in telling it I didn’t want a person in a white hat and another in a black hat. So it is ambiguous, and it does make a lot of people uncomfortable.”

Harrison shifts her baby, who has started to giggle in her sleep. “The other part of it,” she continues quietly, “is I just seem a little too much like everybody else. If I weren’t married, if I didn’t have children, if I’d written it from my locked cell, if I were marked in some way that was visible, people would have been more comfortable.”

It does seem to weaken one of our last taboos: what’s the point of the incest prohibition if you break it and turn out OK anyway? “Of course I am marked by it, but it’s private, I don’t wear it like Hester Prynne’s scarlet letter.”

It remains to be seen how The Binding Chair will be received by the literary community. After being chastised for spilling her guts in The Kiss, Harrison has returned to a genre, the quiet world of historical fiction, that allows her to mine her trademark preoccupations in relative safety. Though Harrison’s prose is as controlled and precise as she herself is poised and articulate, the book overflows with a cast of troubled characters struggling to keep their guards up. And the drive toward self-revelation is most alive in May, who refuses to live out the remainder of her life with an awful secret unspoken. The Binding Chair leaves us wondering where Kathryn Harrison’s overheated obsessions might take her next.

LINKS TO INTERVIEWS:

http://partners.nytimes.com/books/00/05/21/specials/harrison.html